Looking at Models

By Charlotte Kent, PhD

GENERAL INTRO

Looking at Models examines the concept of the “model” in contemporary culture, spanning art history, scientific representation, and the accelerating influence of AI and computational systems. The exhibition brings together artworks that adopt the human figure as a visual and conceptual structure across diverse technologies including photography, ASCII, text-to-image/video AI, and more.

Models appear in the make of a car, on a runway during fashion week, through the expectations we bring to each day, and now across the spectrum of “AI” in Large Language Models, diffusion models, transformer models producing texts, images, scientific discoveries, and more for application in the world. Models are everywhere and seem to do anything and everything. The concept of a “model” originated in the arts as a reference for creating something else, but by the 19th century it spread to science and social theory to explain how things work, and by the 20th century was an ideal to embody, propagated by culture and media. Models may imitate, formulate, symbolize, simplify, identify, idealize, demonstrate, describe, abstract... If models are representations of something, the word itself seems to represent the quality of variety.

The ideas driving this show are inspired by many intellectual models – conversations with colleagues in person, by email, across articles, informing my current research on the models that undergird so-called AI agents and how models of agency differ across disciplines. Also informing the show are observations drawn from two earlier exhibitions: A Working Model of the World (2017) curated by Lizzie Muller and Holly Williams, and What Models Make Worlds: Critical Imaginaries of AI (2023) curated by Mashinka Firunts Hakopian and Meldia Yesayan. The first considered, like this one, the practical and philosophical role of models in human experience, investigating the trade-offs of models’ inevitable application alongside their potential for reflection, experimentation, innovation, and instruction. The second likewise considered the world making import of models, through the particular impact of large language models and image generators. This show shifts from an emphasis on models’ worldmaking to the personal impact models have on each of us.

Not all of the artists in Looking at Models use generative AI, but all of them ponder how statistical models proliferate a lot of other conceptual and psycho-social models. Though the data sets that undergird large statistical models extracted information about us, we aren’t present within these systems…their internal logics ignore how we matter and materialize the data they collect. The recurring figuration across these art works aims to reinsert us both by questioning how we are proposed as models for the models, as well as what the models model for us. In so doing, the artists ask about our presence in other complex systems like techno-capitalism, various forms of mass and personalized media, post humanism, and art.

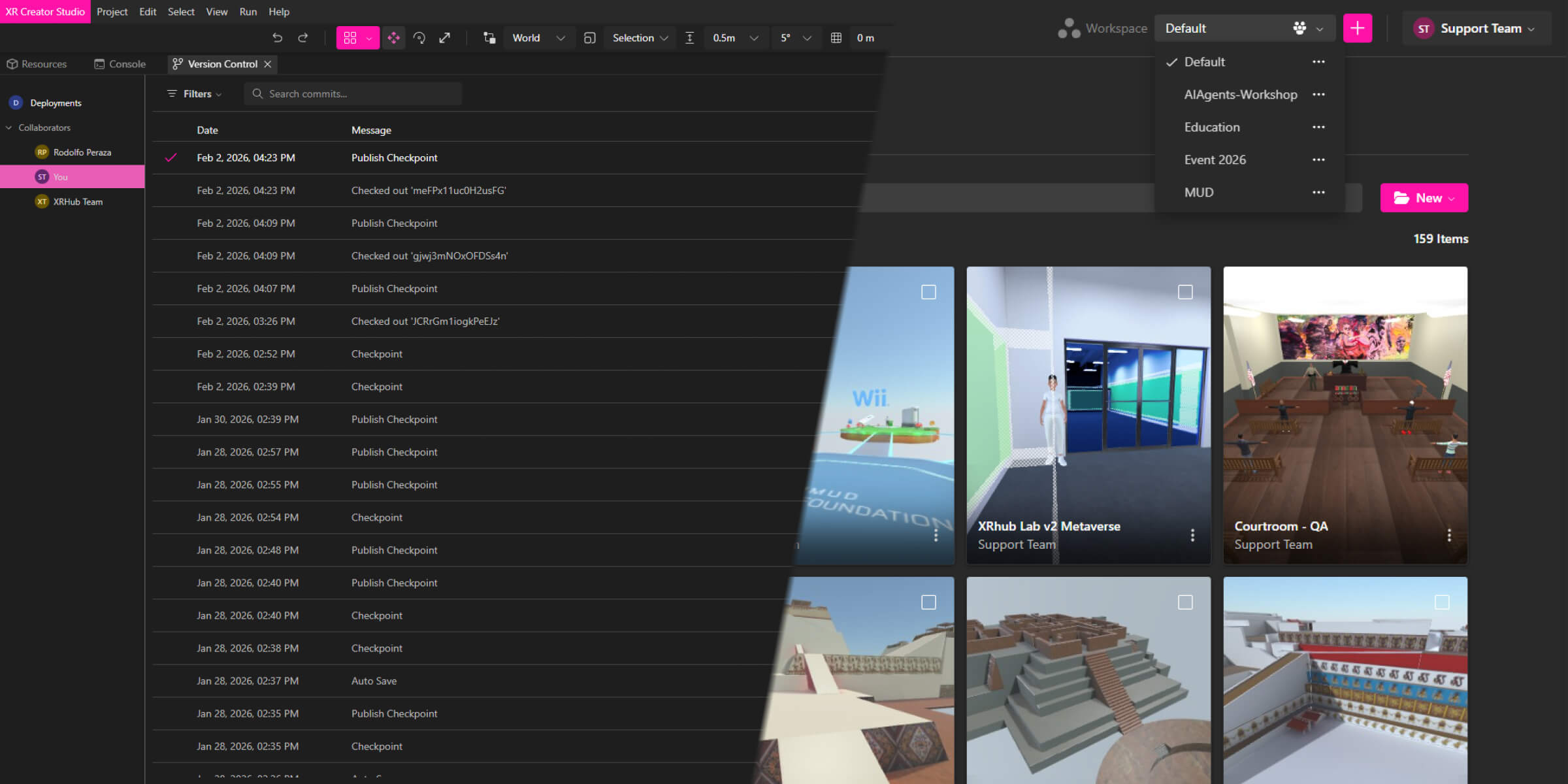

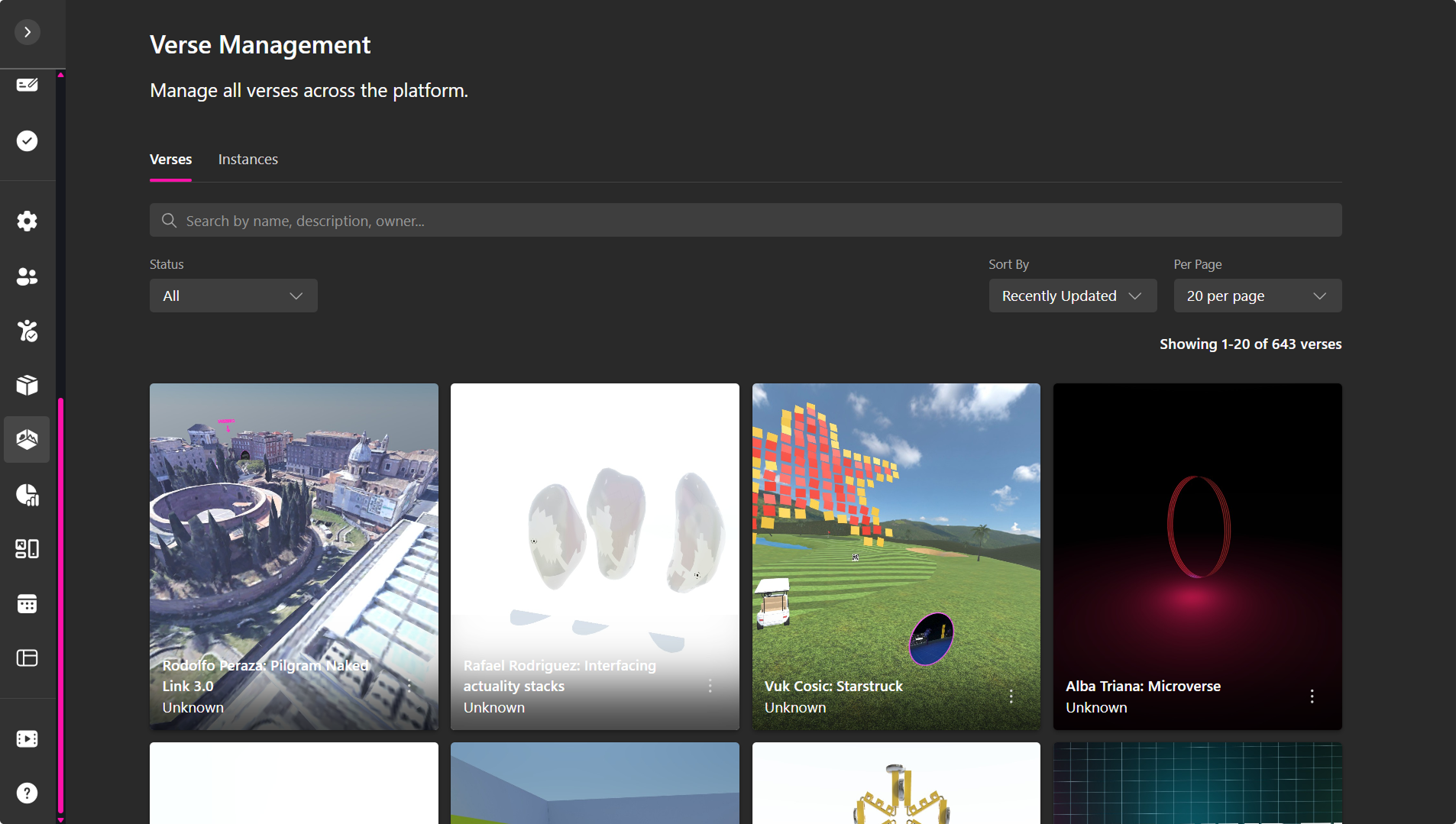

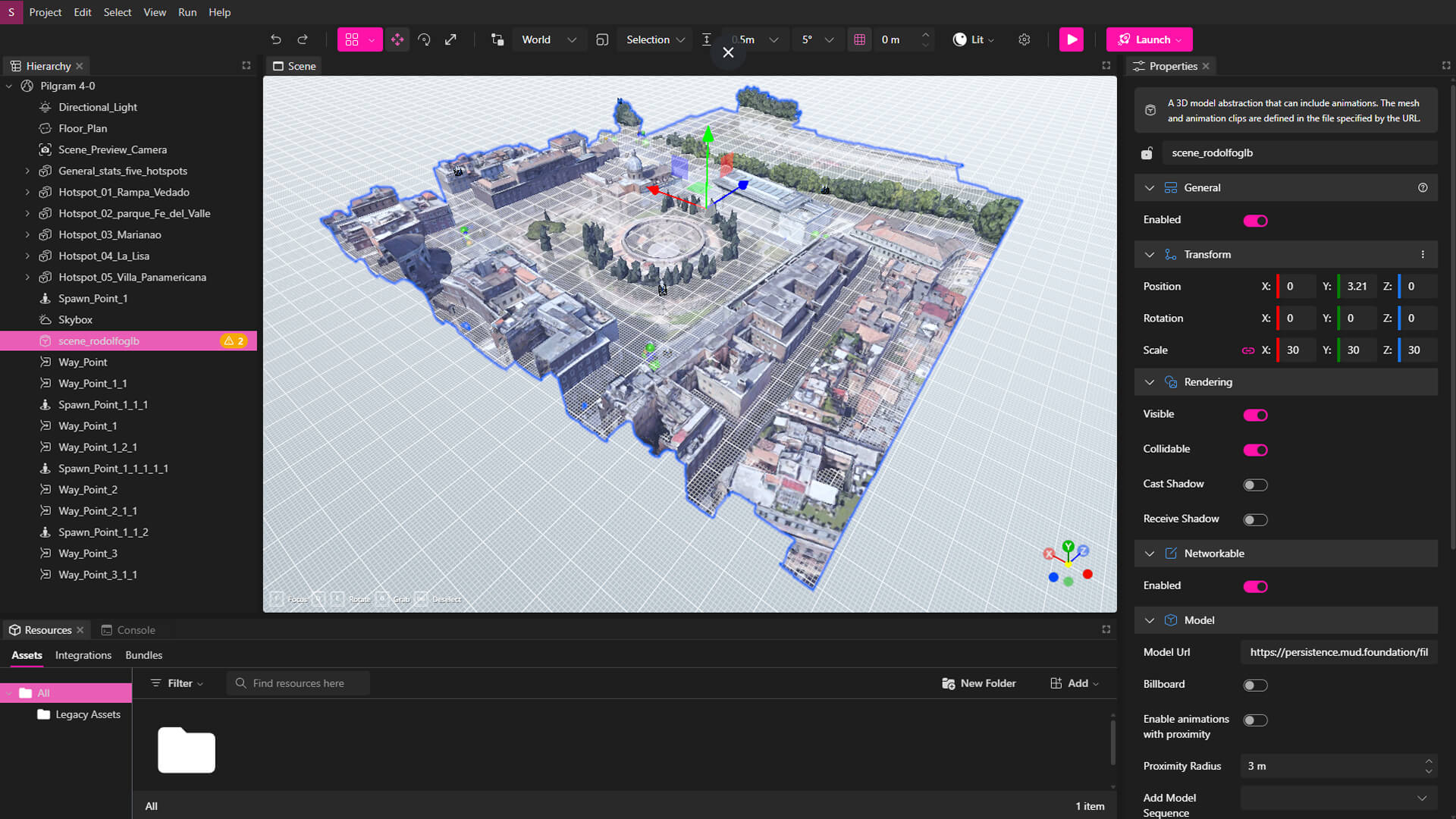

Using MUD Foundation’s Data Interceptor vehicle to project the works across walls in different neighborhoods of Miami introduces a different model. The car’s recognizable model shifts its associated police authority to do something communitarian by sharing wifi, art, and conversation. Cars are widely associated with mobile privatization, which contributed to an ideological turn fifty years ago that claimed distance and isolation made us safer from the rough streets. So came the marketing for a third place and residual doubts about convening outside. Those models served few. On this side of the 20th century, now a quarter into the 21st, taking to the streets may help us look at the models we have been given and find the people, politics, and practices for the models we seek.

WHAT ARTISTS MODEL

The artists in Looking at Models critique, expose, and reinsert human presence into systems dominated by computational and psycho-social models. The concept of a model evolved to become an ideal to embody, often synonymous with beauty standards and consumerism, a role amplified by visual culture and celebrity. Gretchen Andrew addresses this by creating paintings that show the invisible scars left by social media filters that seek to perfect us. Her work reveals the proliferation of both algorithmic and aspirational models that shape expectations of social validation, a concern for many of the artists in the show. The artists expose the opaque logic and construction of “AI” systems as well as the myriad ways that models serve as invisible architectures that govern behavior and perception.

Maya Man in StarQuest (DanceEdit) reflects on the structures of training and optimization that govern both statistical models and competition dance. From initially developing the project through a biographic identification with the dancers in the popular reality TV show Dance Moms, her work shifts from absorbing the audience’s gaze into authorship: she becomes the choreographer not only of movement but of perception itself. By diversifying her cast and reorienting adult figures to the margins or backs of frames, she subtly rewrites the power dynamics of the original show. The project takes the hyper-curated, performative labor of the dance floor and equates it with the digital labor required to maintain the perpetual, first impression demanded of online presentation and, like the Facetune Portraits of Gretchen Andrew, StarQuest denies the illusion of perfectly rendered outcomes. If algorithmic models typically serve to derive exact predictions and the best of all possible worlds, Man uses AI to highlight the artifice in such promises. Through the technologically generated analogy of competitive performance, Man reveals the underlying social model, asking viewers to consider what is lost when complex identity is compressed into simple derivatives.

The conversation around "AI" stems from cybernetics, a post-WWII model that reduced humans to schematics, focusing only on observable behavior (inputs and outputs) and resulting in the elimination of the subject, or self. Fabiola Larios exemplifies the many critiques of this condition, by focusing on how code and surveillance aesthetics turn our interactions into data and our bodies are turned into interfaces. In scroll_over(me), the artist shows how models silently script our choices and sense of self. This subjectless nature generates ethical problems because the subject remains present. Surveillance intersects with a representational burden: when mainstream media underrepresents or stereotypes identities, an expectation—explicit or implicit—to correct these portrayals through posts can surface. Furthermore, the political landscape surrounding immigration heightens the experience of being watched online. With documentation that DHS, ICE, and local law enforcement agencies use social media monitoring tools, communities with strong ties to Mexico, or any part of Central and South America, feel this acutely; women involved in activism face disproportionate monitoring. Racist profiling in which Latinx appearance is equated with being an immigrant extort a type of self-censorship and a form of strategic silence. This creates a high cognitive and emotional load around even mundane social media actions. scroll_over(me) recognizes the schema that maintains LatinX women as both overlooked and looked over.

.jpg)

Emi Kusano examines how identities have become raw material commodified by market demands. In Algorythm of Narcissus, she revisits the narcissistic tendencies generated by social media and exposes how surveillance capitalism in the age of AI deprives us of the possibility to develop an authentic self-expression. Acknowledging how largely Western-inscribed image ecologies assert a cultural hegemony, Kusano plays with the outer ethics of representation—how technological systems encode and distort cultural identity, flattening diverse values into algorithmic expectations. Invoking the ancient Greek myth, Algorythm of Narcissus asks the viewer to dwell with what we see reflected back to us, and consider the discomfort of partial understanding, the possibility of encountering something untranslatable. This illustrates the risk in statistical modeling generalizing and condensing diverse human experiences into predictable, consumable products.

The constructed nature of the data sets that undergird public generators are laboriously emulated by Michael Mandiberg. Their Taking Stock video iterations draw from millions of stock photographs—significant parts of AI training data—to show the layered images that form the foundation for any generated output. In scouring these images, Mandiberg discovered that Ukraine and Belarus had each produced more stock photographs than the United States, the vast majority of which are tagged as white/caucasian/European. Before the EU or the USA debated including Ukraine as a cultural ally, their image market was already situated there. Our models aren’t who we think they are, asking us to revise mental models in significant fashion.

Statistical models are defined as purely mechanical, following patterns with no awareness or purpose, and tending toward the general and categorical when they clearly serve a market demand. Boris Eldagsen, in Measurement is King, uses AI-generated material to question the role models of today’s tech bros and critique the illusion of control that quantification proposes. Using the glamour and appeal of 1940s Hollywood musicals that romanticized the working class, he situates the media enthusiasm surrounding corporate rhetoric and the AI boom as a Kafkaesque frenzy, recalling how ideology, bias, and desire appear across technological, cultural, and socio-economic models.

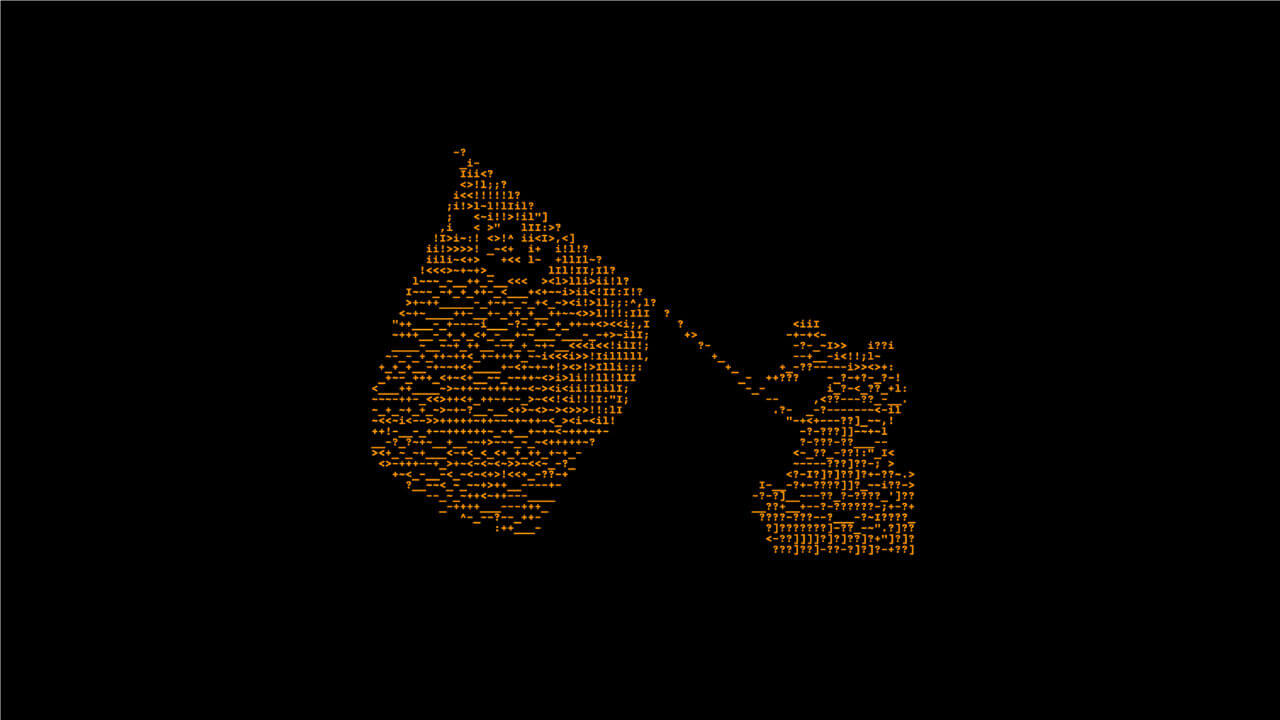

As a critical media artist, Vuk Ćosić similarly comments on the megalomania of billionaire tech bros (Elon and Zuck) who position their technocapitalist projects as models of patriotism and success in History for the Blind. The works suggest that rallying under flags usurps critical consideration of what the flag is being used to model, and the audio rendition of the ASCII images invites us to question narratives delivered by recursive babble across mass and social media.

In Cathexis Core: Flag, Fire, Flower, Carla Gannis references a psychoanalytic concept for the investment of mental or emotional energy given to a person, object, or idea, which propels us to question how we view, value, and emotionally connect with the models presented in contemporary culture. Gannis reinserts the subjective dimension back into the highly objective, statistical world of AI models, forcing an ethical consideration of where we choose to direct our most valuable resource: our mental and emotional energy. Various forms of artificial adornment allude to their biological and mineral references, blurring how we read what we see as face turns into flora into fauna in a recursive loop. This transmogrification comes to represent the generative models that churn planetary materials across their supply chain ecologies to morph into new technological feats, connecting the models to the broader material costs of technology. By connecting Cathexis to Core, Gannis implies that the emotional investment we place in these technologies (the computational models) has a core, material reality, drawing attention to the full, non-virtual cost of our fascination. We live in relationship and choose how.

James Bridle created his own autonomous car in 2017—writing the software, training neural networks, and outfitting the vehicle with cameras—rather than accepting a singular, corporate vision of technological progress, much as MUD Foundation did with the Data Interceptor that turned a police car into something far removed from a model of authoritarian surveillance. In Autonomous Trap 001, Bridle uses a salt circle to introduce a pre-technological epistemology that disables an autonomous system, exposing the limits of machine learning and its inability to interpret and resolve conditions of a dilemma. The salt ring of solid and dashed lines immobilize the autonomous vehicle that can only interpret the visual cue one way. Recorded near Mount Parnassus—a site dedicated to the Muses—Bridle’s gesture creates a dialogue between the historically complex interpretive depth of understanding and contemporary machine learning. The car is not just trapped by a rule; it is encircled by a crucial yet mundane substance, one that traces a history of human meaning-making. It undermines the aura of invincibility surrounding AI by showing that the most ordinary material can reveal its fragility. What is immediately comprehensible to humans (a playful trap, a ritual line) becomes an absolute barrier to the machine model. Salt exposes the gap between embodied, cultural understanding and algorithmic reading.

The artists’ works collectively construct a critique of the models we have been given, presenting them not just as scientific or computational tools, but as powerful forces that establish ideals, ideas, and ideologies that permeate cultural and psycho-social existence. Humans form elaborate internal models about people and places, but can shift them in response to situation dependent behaviors and events. The exhibition itself also seeks to model collaborative potential by using the MUD Foundation’s Data Interceptor vehicle to project works across Miami, shifting the car's association with police surveillance or mobile privatization to a communitarian act of sharing art and conversation. Ultimately, Looking at Models seeks to make evident the generalizing nature of models and encourage a more critical look at all the models we hold.

WHAT IS A MODEL?

In general, a model is aspirational, something to be copied, a point of reference. Nelson Goodman in The Languages of Art described a model as “something to be admired or emulated, a pattern, a case in point, a type, a prototype, a specimen, a mock-up, a mathematical description – almost anything from a naked blonde to a quadratic equation – and may bear to what it models almost any relation of symbolization” (1976: 171). It’s notable that Goodman includes “a naked blonde” as one of his most specific examples of a model, because though he recognizes the diversity of models, the implicitly gendered figure circulates in the cultural imaginary. It also recalls the sketches of the idiosyncratic physicist Richard Feynman, whose mathematical musings are interwoven with figure drawings. They come in many forms and serve different purposes across fields. Invariably, models collapse from sheer exhaustion.

In the arts, models serve representational purposes, helping visualize and reference; they can be human muses and historic influences. In design, the most common models are material, typically altering scale in architecture or showcasing incomplete products for tech demos. Conceptual models explain and organize complex ideas, potentially adopting rules of logic to structure an idea or developing theoretical infrastructures that describe social systems, as we find in Kant, Freud, Marx, to name drop some pervasive academic allegiances. Educational and ethical models set standards and guides for behavior and practice.

Often less familiar to general audiences are the particularities of models beyond the humanities. Scientific models present an extrapolation from regular and repeated observations of phenomena, but these models can also exist as paradigms inculcating methods of practice and preferred metaphors as the notable historian of science, Thomas Kuhn explained in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962). Mathematical models appear as equations and formulas; computational models use data and algorithms to predict outcomes, from weather forecasts to economic outlooks. So many models!

Psychologist Kenneth Craik first used the term in 1943, suggesting that the mind constructs small-scale models of reality that it uses to anticipate events. An important systems dynamics thinker, Jay W. Forrester explained that “a mental image is a model” and that “all of our decisions are taken on the basis of models” (Andrews et al: 2022, 132 ). We need to be able to model the world to step outside, but reliance on the familiar can impede our ability to notice subtle or radical changes.

Philip Johnson Laird developed mental model theory in the 1980s, which described the process of simplification and abstraction that people adopt for things whose details can be overwhelming, “particularly modern socio-technical systems,” (Andrews et al: 2022, 131). Understanding the mental model, however, requires a model of that model and depends on “(1) A system, (2) an engineer’s model of the system (i.e., the design documents), (3) a user’s mental model of the system, and (4) a researcher’s mental model of the user’s mental model” and it may provide an understanding that is “subjective or objective, qualitative or quantitative” (Andrews et al: 2022, 133). Every model has multiple models operating within it. It’s turtles all the way down.

The word “model” comes from the Latin modulus, meaning a small measure or standard, and it originally referred to something that served as a pattern or example to be copied. In the 15th century, the term became common in the arts and architecture, in reference to a physical or visual example. The Enlightenment and rise of industrialization expanded the term’s use into science and engineering, where it meant a simplified representation of complex systems, as in a mechanical model. The interest in order and categorization across the 19th century slipped the term into social science and economics, as in a model of government. Around the 1850s, a model began to describe people displaying clothing in Parisian fashion houses. This may have contributed to the idea of a person as an ideal or example to imitate, which exploded with the visual culture of the 20th century, due to advertising, photography, and celebrity culture, so that a model became synonymous with beauty standards, consumerism, and role modeling—linking industrialization, markets, social values, and cultural manners.

There is no model of a mode.

A CYBERNETIC MODEL: No You in AI

The conversation around “AI” stems from ideas propagated at a series of post World War II interdisciplinary convenings, known as the Macy’s Conferences. They introduced the concept of cybernetics and established a model of the mind as a machine. Their reductionist approach simplified humans to schematics. The internal condition of the human mind, including thoughts and feelings, was dismissed because it was deemed inaccessible; human consciousness was a black box. Therefore, analysis focused solely on observable behavior: inputs and outputs.

The cybernetic methodology arose from the wartime necessity of gaining knowledge of the unknown (such as an enemy pilot or coded messages). A pilot was more likely to react in a predictable way if stressed, and so inundating their flight pattern with obstacles, what we might now recognize as information overload, ensured they behaved as expected. By prioritizing predictable behavior over internal meaning, cybernetics resulted in the elimination of the subject, or self. In this view, the notion of "you" controlling thought or desire vanishes. Instead, the self is conceptualized as the activation of neuronal processes within a self-organized complex system, with subjectivity emerging merely as an effect of various actions and behaviors.

The subjectless nature inherent in the cybernetic model generates significant ethical problems. Jonathan Beller wondered what happens when “from the perspective of information, there are no subjects or objects left, only strategically constituted networks and virtual realms,” such as occur within the calculus of computational systems (2018, 11). Cultivating behavior modification through complex reward constructs for an economic system (widely addressed around addictive engagement, like checking social media) only lacks an ethical context if there is some essential person impacted. When there is no “you,” then there is no subject to harm.

Despite the effort to eliminate the self by focusing on activities and behaviors, the subject reappears precisely when the model fails to account for the unmodeled complexity of others. That cybernetics eliminated the self to focus on behavior didn’t eliminate the assumption that something (some person, mind, being, entity) is there, but allowed its psychological drives to be sidelined. Sort of. Mechanizing the mind in this way supposes a mind can exercise power over this mind-as-artifact “to reproduce and manufacture it in accordance with its own wishes and intentions” with norms imposed that instill meaning and purpose to this mechanization’s mechanics. Yes, it’s convoluted. That’s how we find ourselves with “AI agents” and a discourse concerned with how we might “speak of ethics, conscience, the will—is this not to speak of the triumph of the subject?” (Dupuy: 2001/2021, 20). But now the subject of concern are the models and not you, or the many humans around the world whose rights remain unaddressed by these fantasies.

Building models off models sets the stage on which we are even poorer players, no longer strutting and fretting, rambling and raving, but struck dumb and frustrated by a fourth wall we can’t break that signifies more than we do. Personalizing a model doesn’t evade the design ideologies that segment who and what matters.

British cybernetician John F. Young warned in 1968 that the field risked becoming “an up-to-date form of Black Magic, as a sort of twentieth century phrenology,” where activities, rather than internal consciousness, determined the subject (Kline: 2015, 182). Instead of bumps on the head, activities determined the subject, or what constitutes the being that perceives itself as a subject. The wartime model of cybernetics bled into a culture that has been struggling with the existential crisis of this determinative model, one that manufactures a contrived participation.

MODELS TODAY

Now, models appear in general conversation about “AI” with terms like Large Language Models, diffusion models, transformer models producing texts, images, scientific discoveries, and more for application in the world. Language conveys conceptual models and technology often adopts familiar terms and images to ease adoption, making skeuomorphic analogies that obfuscate significant differences. User friendly isn’t always for the best. To avoid the metaphoric dissemblance of terms like language or reasoning when describing these new machine processing and predicting constructs, I refer to them as large statistical models.

Conceptual models, psycho-social models, physical models, and mathematical models can’t be defined by the same process or criteria. All appear in the design of the statistical models that impact our lives. The packaging of these statistical models, however, evades the models on which they were built. These models have their own set of problems we need to address too.

As the anthropologist Genevieve Bell explains, “a set of implicit, tacit, cultural assumptions that are unvoiced” proliferate around AI. The assumption of AI’s unmarked status is made evident when the term gets marked with a descriptor, like Buddhist AI or Indigenous AI, or when media amplify narratives of anxiety (coming from whom?) about “AI” from “China” …then suddenly the cultural marking surfaces, but even that is laughably simplistic. Put people together from Beijing, Taiwan, and Hong Kong as well as diasporic Chinese communities from Southeast Asia and Korea, and the political tensions would be palpable.

The surface-level similarities used to compare models in art and machine learning occur because words like learning, generate, or imagine endow an impression that machines are like us. We see creativity, intention, and expression in AI-generated outputs, projecting human qualities onto them, yet the reality is purely mechanical: the models follow statistical patterns with no awareness or purpose. We unconsciously experience wish fulfillment, feeling a sense of mastery or creation without effort, while the outputs’ designed similarity to human expression triggers the uncanny, a subtle unease at the familiar-yet-strange.

The irony is twofold. On one hand, we get told that these systems are truly different from us, evidenced by their calculating speed to arrive at information possibilities that some call intelligence. In that precise moment, these systems also become just like us and deserving of the rights and care we would afford any human. The AI agent conversation can then unfold about all the legal and ethical dilemmas these systems present, completely distracting us from the questions of rights and humanity that so many humans around the world don’t experience.

People worry about algorithmic models because they can reflect or amplify biases in their training data, threaten privacy, and make opaque decisions that affect real lives. They can automate jobs, manipulate opinions through targeted content, and pose safety risks if misused in critical systems. Widespread AI use raises ethical concerns, shifts societal norms, and concentrates power in a few organizations, giving them outsized control over information and resources. But, how do these systems do these things? Are these dubious or dangerous operations merely side products of their design? The concern isn’t just about smart machines—it’s about how humans design, deploy, and oversee them, and the real-world consequences of errors, misuse, or bias. The models aren’t modeling themselves.

A POWERFUL MODEL: Some Science Stuff

A diffusion model (for example) is a model, in a technical sense, because it mathematically represents and simulates a process—specifically, how data can be gradually transformed from noise into a structured pattern. A generative model resembles artistic modeling in its creative output, but it is fundamentally algorithmic and probabilistic. The problem of distinguishing representation, simulation, and idealization become rampant. Not only do algorithmic models and artistic models serve different purposes in relying on input to produce abstractions of reality, but even similar algorithmic processes can have different purposes and so do different things with widely varying social impact.

The power of statistics infuses our willingness to conform to these models. The empirical sciences laid a claim to truth over a century ago through a type of logic that isn’t occurring in quite the same way within these computer science systems. The so-called hard sciences observe phenomena to develop data that they test based on a deductive hypothesis (a general principle is applied to a specific situation); when the findings are observed as regular and repeatable they extrapolate their specific observations to be general—an inductive move. Probability theory “offered a way to treat inductive inference as regular and repeatable in practice,” which is to say that probability theory allowed a specific thing to indicate future recurrence because an inductive hypothesis treats the single specific thing as if it already existed within a general principle confirmed by repetition and regularity (Stark: 2023, 38). So the day that you were mad and unexpectedly listened to heavy metal suddenly makes your music platform introduce much more of that. The problem is “Individual human actions cannot be reliably aggregated into general and repeatable empirical rules” (Stark: 2023, 36)

The humanities tend to find interest in the marginal, unusual, and unexpected from which they produce stories…for better and worse, of course. Its conjectural because the conclusion derives from incomplete information. That process is known as abductive reasoning. Psychoanalysis is full of these moments; insights or errors gleaned from a detail. Some great literature takes a moment in time and spins out a tale that speaks to us in part because we don’t accept it as inductive but a kind of general principle from which we deduce particular similarities to our own experiences; it feels universal but not because we have exactly replicated the story to confirm it. By referencing Carlo Ginzburg’s notion of conjectural sciences, Luke Stark explains in “Artificial Intelligence and the Conjectural Sciences” (2023) how machine learning systems presume the empirical science processes of deduction and induction, but are deeply dependent on the conjecture of abduction.

When the humanities tried to ground themselves in rules and laws, the general and categorical, they abandoned the significance of espousing the singular and particular. The rejection of the genius and death of the author would necessarily be part of this process. Yes, it is important to realize that people make works coming from a context and community, but celebrating someone as particular also resists the statistical modeling that swallowed the social world. The arts do great work with abduction but we might be wary of having social structures like governmental processes doing the same.

The artists thoughtfully using these large statistical models make evident their generalizing nature and allow us to tell our own story about how we do and don’t fit into these broad scope narratives.